Starting with Nikola Tesla’s invention of a radio-controlled boat in 1898 to the modern unmanned vehicles today that operate in space, in the air, in the oceans, and on the ground, unmanned systems rise to a $100+ billion industry is nothing short of stunning, (Desjardins, 2016). This tremendous growth has brought amazing applications and awe-inspiring images; from the ability to map the deepest parts of the ocean to images and information of the universe that help support theories that were developed over the last couple thousand years. Although these results and immediate success have created multiple unintentional complicated situations and concerns, through regulation and innovation most platforms have prospered and are meeting these challenges head on.

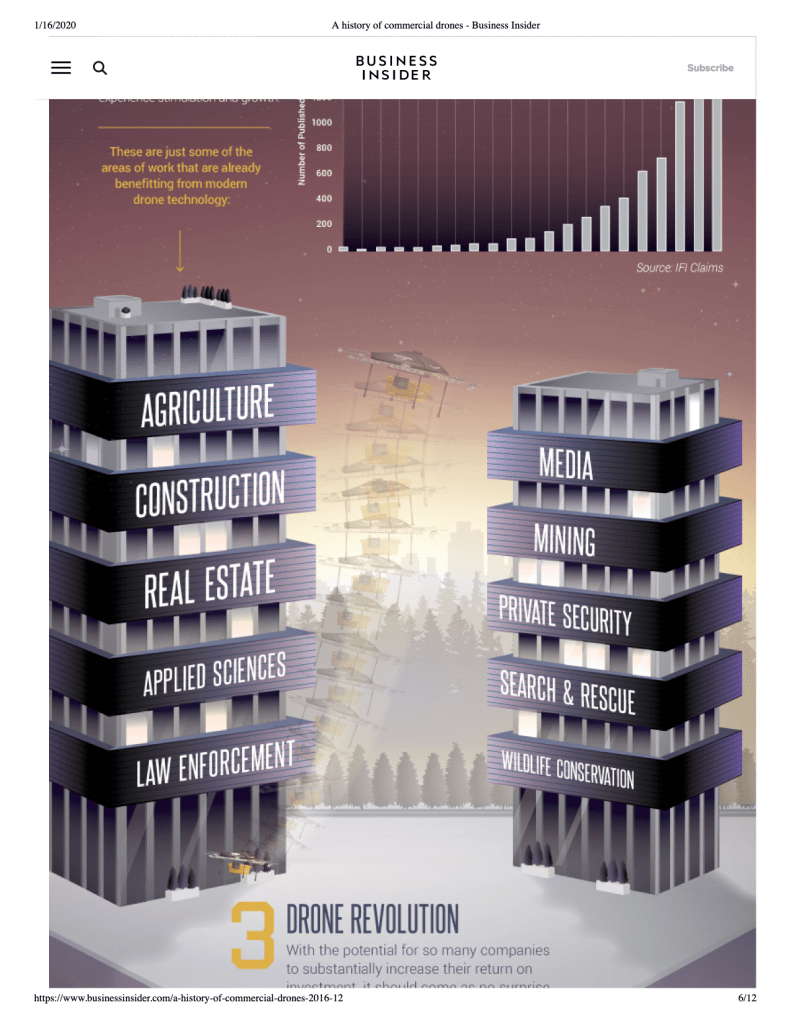

Probably the most widely used and controversial (with regards to privacy and safety) application is aerial photography, monitoring and inspection. Prior to unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), aerial photography, monitoring, and inspection was performed primarily by airplanes, satellites, and helicopters. Anybody who has paid to use one of these methods knows that it can be extremely expensive. Early in this century UAV technology was advancing to the point where small UAVs were gaining interest by hobbyist. They finally had the ability to fly around their neighborhoods, places of impressive beauty, and outdoor sporting events (skiing, surfing, mountain biking, etc.) and take pictures and/or video for a very reasonable price, and the hobbyist were entirely in control of the product. Many people quickly recognized that there was money to be made with this new technology and the commercial drone industry was born. In 2006, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) recognized the potential of non-military, non-consumer drone applications and issued the first commercial drone permits, (Dormehl, 2018). With the development of wifi capabilities, increased battery life, 3D mapping, obstacle avoidance, and many other technologies, the markets impacted by aerial photography continues to grow. Some of the areas of work benefitting from commercial drone technology are mentioned in the following picture.

Initially, the regulations were few and not a primary concern, because the drone’s abilities were limited and the relatively small number of drones used were not considered a threat. One thing to consider; the first drones didn’t have the capacity to use a camera, therefore there was a lag in time when the general public realized that their privacy could be compromised by the innocent drone flying outside there house, business, or guarded operation. Resulting from the safety and privacy issues, the FAA grounded all commercial drones in 2012. Their immediate answer to this was the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 which established their Unmanned Aircraft Systems Integration Office. Congress had tasked the FAA with integrating unmanned aerial systems into the national airspace by September 2015, (Luppicini & So, 2016). During this time drones were ungrounded with more restrictions but concerns still existed. An Australian woman complained that a drone captured her sunbathing topless and the resulting photograph appeared in an ad for a real estate company, (Matyszczyk, 2014). “A White House radar system designed to detect flying objects like planes, missiles, and large drones failed to pick up a small drone that crashed into a tree on the South Lawn early Monday morning,” (Schmidt & Shear, 2015). These are just a couple of examples that took place during this time of transition to higher regulation.

On Tuesday, June 21st, 2016, the FAA released Part 107 which provided a certificate as well as operating rules for drone operators who do not fall into recreational drone operations. Some of the rules included are maximum groundspeed, maximum altitude, operations in different types of airspace, responsibilities of pilot in command, and the list goes on, (“Ultimate Guide,” 2020). With these regulations, the drone industry has become more innovative and the commercial drone users have complied, therefore mitigating the primary concerns at this time. To further help this cause, the FAA is looking to launch a nationwide system to track drones (over 250 grams) in the sky in real-time, as well as connected pilot ID’s, (Mogg, 2019). The story of commercial drone use for aerial photography, monitoring, and inspection is beyond success; it was only a dream until the turn of the 20th century. With its unlimited possibilities, the entire world will benefit. “At the end of the day, the impact of commercial drones could be $82 billion and a 100,000 job boost to the U.S. economy by 2025,” (Desjardins, 2016).

References

Desjardins, J. (2016, December 15). Here’s how commercial drones grew out of the battlefield. Business Insider.Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/a-history-of-commercial-drones-2016-12

Dormehl, L. (2018, September 11). The history of drones in 10 milestones. Digital Trends. Retrieved from https://www.digitaltrends.com/cool-tech/history-of-drones/

Luppicini, R., & So, A. (2016). A technoethical review of commercial drone use in the context of governance, ethics, and privacy. Technology in Society, 46(2016), 109-119.

Matyszczyk, C. (2014, November 17). Peeping drone captures woman sunbathing topless. CNET. Retrieved from https://www.cnet.com/news/peeping-drone-captures-woman-sunbathing-topless/

Mogg, T. (2019, December 2019). FAA proposes nationwide real-time tracking system for all drones. Digital Trends. Retrieved from https://www.digitaltrends.com/cool-tech/faa-proposes-nationwide-real-time-tracking-system-for-all-drones/

Schmidt, M., & Shear, D. (2015, January 26). A Drone, Too Small for Radar to Detect, Rattles the White House. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/27/us/white-house-drone.html

Ultimate Guide to FAA’s Part 107 (14 CFR Part 107). (2020, January 17). Rupprecht Law. Retrieved from https://jrupprechtlaw.com/faa-part-107/